Wabi-Sabi: Finding Beauty in the Imperfect

You might’ve come across the term wabi-sabi lately—maybe in a design magazine, maybe on a Pinterest board filled with sun-faded timber and uneven ceramic forms. While it’s gained popularity in the world of interiors, wabi-sabi is far more than a style trend. It’s a deeply rooted Japanese philosophy that gently encourages us to see the beauty in things that are imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.

At its core, wabi-sabi is about quiet appreciation. “Wabi” speaks to simplicity, humility, and a kind of understated elegance. “Sabi” refers to the beauty that emerges with age—think weathering, fading, softening. Together, they form a way of seeing and living that values authenticity over perfection, and timeworn beauty over anything too polished or pristine.

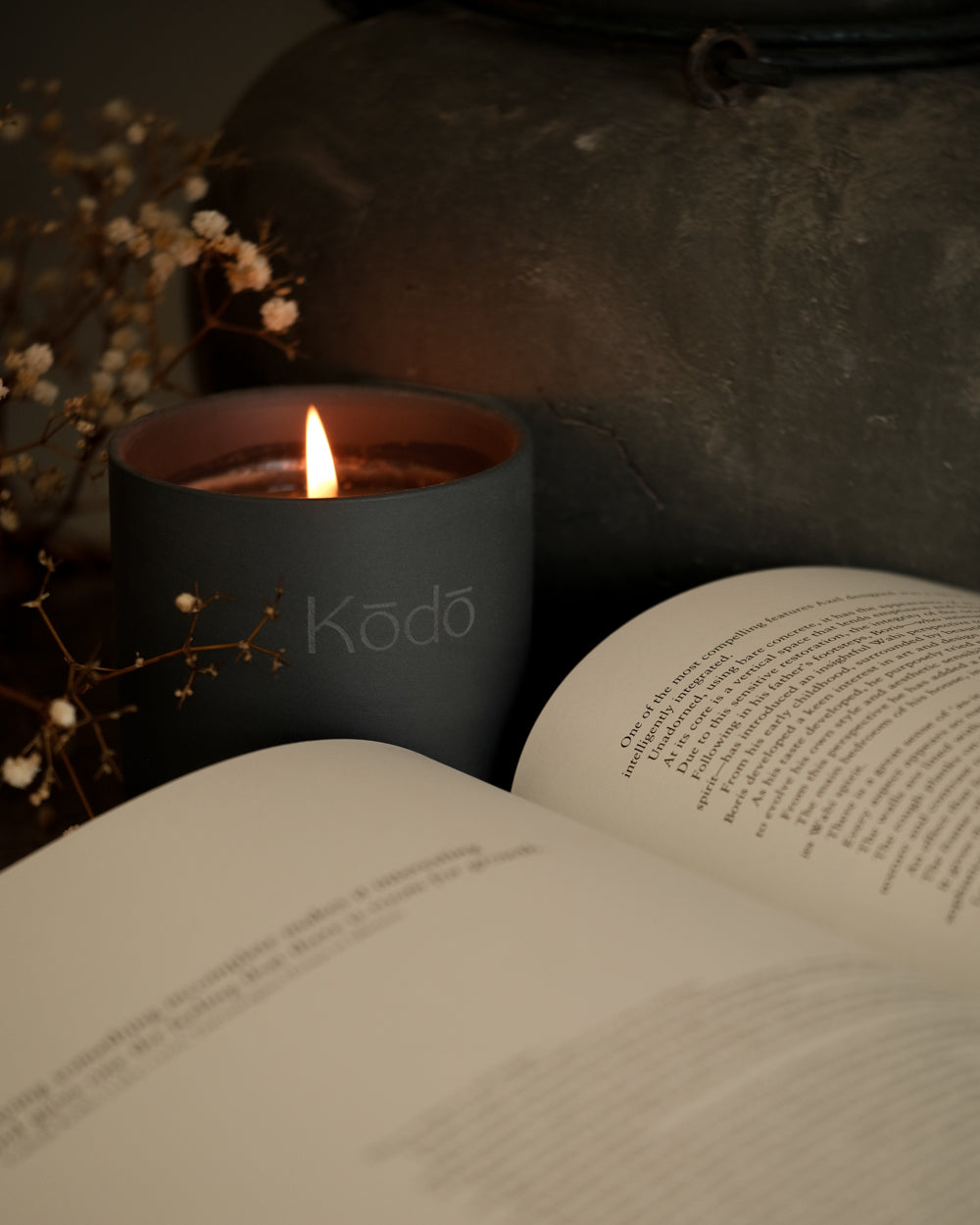

This aesthetic is woven through Japanese culture, especially in traditional arts like tea ceremonies, ikebana (flower arrangement), and handcrafted pottery. It’s not about deliberate design flaws or artificial ageing—it’s about letting things evolve naturally. It’s about materials that change over time: timber that silvers under the sun, stone that holds the memory of rain, ceramics marked by fire and earth.

Wabi-sabi also has a quiet connection to Japan’s landscape. In a country shaped by seasons, natural disasters and shifting weather patterns, there’s an ingrained understanding that nothing lasts forever. Life is fragile. Homes built from wood and earth aren’t made to resist time, but to live with it. That awareness has shaped an aesthetic that welcomes transience instead of denying it.

In the modern world, where we’re often pushed to keep up—always refreshing, always upgrading—there’s something deeply comforting about this. Wabi-sabi reminds us to slow down. To stop chasing flawless. To let the edges soften. It gives us permission to look at what we already have, or who we already are, and say: this is enough.

There’s a quiet kind of beauty in the way a ceramic surface wears out over time. Or how the grain of timber deepens with years of weather. Or how a handmade object carries the imprint of its maker. These aren’t imperfections. They’re stories. They’re signs that something has lived, breathed, been touched by time and the elements.

And maybe that’s what makes something truly beautiful—not that it’s untouched, but that it has been changed by the world around it.

Wabi-sabi isn’t something you buy or replicate. It’s something you feel. It’s a softness. A slowing. A quiet reverence for what already is.

Because in the end, nothing is ever truly finished. And perhaps that’s exactly as it should be.